On Model Abstraction in RPGs

Bringing the Game into Focus

One oft-cited problem with simulationist game design, worldbuilding, hexcrawls, and various other dimensions of gaming is the misconception that you need to build out an entire universe in great detail. This is obviously infeasible, and typically cited as a reason why worldbuilding is unnecessary, hexcrawls are too much prep work, and real simulation is impossible.

The answer of course is not particularly novel nor anything that I have a special claim to, but it is worth articulating (and many thanks to the Arbiter of Worlds for establishing a clean foundation). The answer lies in the concept of abstraction — not in the sense of abducting the general case from the particulars, nor quite that used in computer science, but specifically what is called “model abstraction,” as it is used in the (real world) development of simulations. I find this definition particularly useful, from Model Abstraction Techniques:

Model abstraction is a way of simplifying an underlying conceptual model on which a simulation is based while maintaining the validity of the simulation results with respect to the question being addressed by the simulation.

For an easy example, we might ask whether D&D models bathroom breaks for adventurers. Critics of simulationist principles have argued that it does not, because they are never explicitly addressed. But such is the domain of abstraction: such concerns are simplified as part of a more general model, maintaining verisimilitude and coherent outcomes in the broader picture.

Consider that characters in a dungeon must rest for a turn each hour, or take mounting penalties. Bathroom breaks can be assumed to take place abstractly within such time slots, and if missed their inconvenience factors into the existing framework of penalties. This is not because such rests are bathroom breaks by another name; they also offer adventurers a chance to check wounds, drink water, and catch their breath (other things not explicitly modelled in the games rules but that nonetheless take place). Rather, the rest each turn is an abstraction, which maintains the coherence of the game world without requiring trivial things to be tracked and accounted. For more characteristics of abstracting some factor rather than ignoring it, see Which World Do We Simulate?

I find it valuable to note here that the game does not suffer at all for such abstractions if they are implemented well. Rather, they focus the game on the aspects that are interesting and important, while preserving the underlying concordance of the game world and the potential for noetic appreciation of verisimilitude. It is not a zero-sum tradeoff between Simulation and Gameplay, but rather a case where improving the Simulation refines and improves Gameplay.

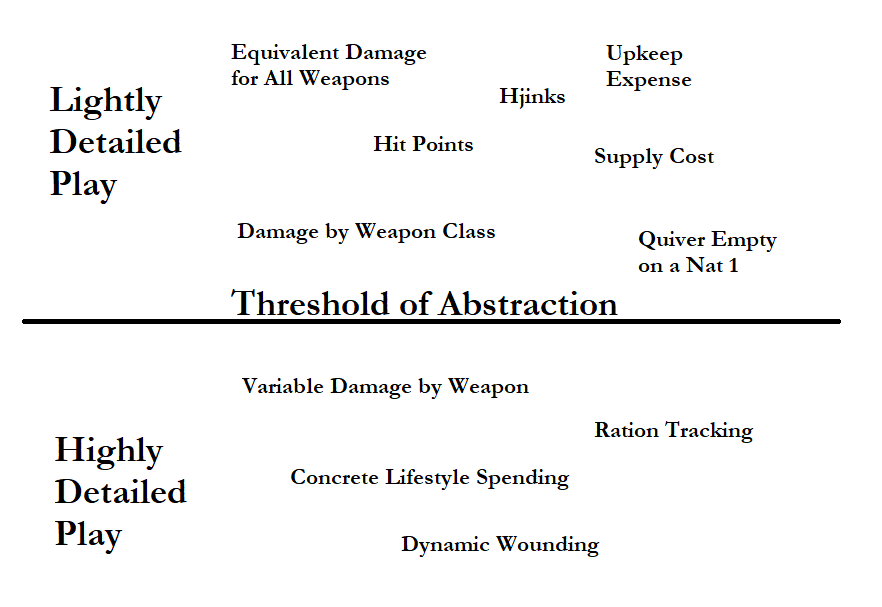

The Threshold of Abstraction

A concept I have referenced often is the “threshold” at which abstraction takes place, that is, the level of detail desired in a ruleset. Compare archaic melee combat in GURPS (where adversaries attempt a specific blow each one second round) and AD&D (where actions play out over one minute rounds and represent the most significant happenings). Both model combat of the same general sort, with a generally “realistic” bent to it though scaling up to superhuman levels of skill, and yet the gameplay experience is dramatically different because of the different levels of abstraction chosen. Even something as seemingly fundamental as what a “hit” is changes: in AD&D, it represents scoring a decisive blow, whereas in GURPS any blow that strikes the opponent is considered a successful hit (which might then be soaked by armor and functionally ignored). Combat in B/X D&D is even simpler than AD&D, with everyone on the same side acting at once and most of the unusual maneuvers such as grappling removed (or rather, abstracted as part of the default option to attack).

Ultimately this difference comes down to a matter of player preference (“player” to include the Judge, naturally) and what is intended to be the core of the game. Wherever the game is mechanically rich, gameplay will tend to settle and focus. Thus, if we intend a game to focus on tactical dueling, it needs a robust system for handling that, and we might conclude that B/X and AD&D are poor options (and En Garde likewise illustrates that even with an elaborate dueling system, if we build in a yet deeper social interaction sphere it needs to be built to channel action back to the dueling unless we wish it to become a game of jockeying for status).

AD&D lacks the detailed resolution to run an interesting game purely on dueling because that is not remotely its purpose. The relatively high threshold of abstraction (and attached mechanical simplicity) it offers makes it much better suited to running combats with dozens of combatants on each side, and shifts the focus of the game away from combat more generally in favor of a well developed exploration component (where it has a lower abstraction floor, i.e. more detailed resolution, than many games).

The Alexandrian discusses a similar phenomenon in the comments of this excellent post, in which OD&D including rules for torches being blown out and listening at doors created such behaviors, and drove dungeon design based on those features. As the game became more mechanically complex, such features lost their pride of place. That’s not a bad thing, but rather a natural result of the scope and depth of the game broadening.

Abstracting Non-Gameplay

If the aspects where a game is mechanically complex ought be those on which it intends to focus gameplay, the reverse is likewise true: those things that aren’t desired to be a significant component of gameplay should be abstracted away (but not ignored).

A game that wishes to model the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings needs rules for rations and finding water; a game that wishes to model fantasy superheroes is likely better off reducing their encumbrance, increasing their lifestyle expenses, and assuming that appropriate quantities are carried. Worlds Without Number seeks a middle ground, where logistics are relevant but not a cornerstone of the game, and its abstract slot-based encumbrance system is very clean and usable to that end (and its horses are noted to have been magically altered to be able to forage in most terrain).

Similarly, while such management has always been a part of classic D&D, come mid-levels divine casters have access to the spells create water and create food, which can functionally replace it. This creates a shift in gameplay, where individual encumbrance is no longer the focus (as discussed in more detail in the Alexandrian article above). Thus we see that even within a single campaign, access to new options allows the game to dynamically reset the abstraction floor and tailor it to the game’s changing focus. Taking advantage of this ability of tabletop games to optimize themselves towards certain experiences through targeted abstraction is a key element needed to achieve TTRPG Supremacy.

The Observable Universe

To tie this back to the original context then, the same principle applies to fleshing out a game world (whether for a hexcrawl, a dungeon, etc.). The area where gameplay will focus needs a low threshold of abstraction (i.e. it’s highly detailed), while more distant areas can be more vague, as well as locales adventurers might visit but not actually adventure (e.g. settlements). What specifically that means will depend on the sort of campaign: when I ran a heist game for a singular Thief player, I detailed a single city fairly precisely, but when running a West Marches game the starting settlement can be very abstract indeed because it’s established as a non-gameplay site.

The observable sphere of the game world is what we need model at all (that which cannot be even indirectly observed has no impact on play, after all). As aspects of the game world take bearing on play more directly, they require higher resolution. I have some notes in my worldbuilding about a grand dragon-empire far to the east that was a rival of the fallen west in days long gone, but whose trade now only extends to intermediary states. It hasn’t been fleshed out much since I first established it, because it’s far enough away to have negligible impact on the setting — though if players decided to sail there (or even to the intermediary states greatly impacted by it), it would have to be fleshed out. As my players’ concerns broaden within the known world as they climb to the highest levels, I know I will likewise need to flesh it out more as one of the key rivals for a reunified western empire. ACKS II formalizes this procedure as “top-down, zoom-in,” and offers more concrete guidance on the approach in the Judges Journal.

This is not by any means a failure of simulationism, nor of worldbuilding. Indeed, it is a success, inasmuch as I have created a setting in which I have a manageable amount of work to do and things off-screen can be abstracted to run in the background without trouble, while still creating faithful outcomes and informing me of when it will need greater development. Nor do I claim it’s terribly original — it was discussed years ago in the Arbiter of Worlds book, and I’m certain many Judges have used it themselves consciously or subconsciously as the only way to really efficiently prepare for a campaign. But I think it is very worth understanding within the same context of useful abstraction used to focus the campaign as mechanics can be, and to be supported by the same simulationist principle.

What this comes down to is that which is proximate to gameplay needs details (generally proportional to the amount of gameplay that will occur there). That which is more distant from gameplay needs to be built out just enough to indicate its impact on the more detailed spheres, and to know what would trigger it needing to become more detailed. This encapsulation of content provides the framework that I believe optimizes the ratio of prep work to gameplay quality.

As an example, an assassin-cult lair in the sewers below the city need not be mapped until players actually go there. Where the entrances to the lair are is important to know, so that the lair can be prepped if players visit that proximity. Likewise, the number and level of assassin-cultists present is valuable to know in advance, because that will determine their ability to impact the world (probably assessed abstractly via hijinks). In reverse, any guardians they retain that won’t leave the lair don’t need to be detailed until the complex is mapped, because they won’t impact the broader world (and if I am getting around to the point of mapping it, the fact that such guardians haven’t impacted the broader setting tells me that they need to be of a sort that can be encapsulated in this manner).

Preserving Isomorphism

The downside of abstracting portions of the game world we don’t want to focus on at the table is that their capacity to handle exceptional circumstances and edge cases is much reduced, and the isomorphism between the game world as we describe it and as it can be rationally inferred to exist may grow strained.

In some cases, this can be resolved by having multiple levels of abstraction in a game with some trigger to switch between them. For example, in the edge case that a high level Cleric is out of slots, he cannot create food and the normal ration management system returns to play. In ACKS, if players enlist the aid of a mercenary army, combat is no longer resolved at personal scale but via the Domains at War mass combat system. For game rules, it is valuable to establish a specific breakpoint when this occurs, by some rational basis if at all possible, to avoid attempts to guide the resolution method from outside the game to gain some advantage (whereas an in-character approach to e.g. attempt to field more men so that the mass battle system is used and your opponent’s weaker command and control structure is overtaxed seems perfectly appropriate). For setting components, that sort of breakpoint isn’t necessary, so long as you’re able to sufficiently concretize abstracted content by the time players start interacting with it.

In other circumstances, we might reason from the model and abduct what it implies to be true about the game world. Take the 2 in 6 chance to be surprised in B/X and derivative games, unmodified by circumstance (unless circumstances would render it wholly impossible, e.g. carrying a light source through a dark chamber). This lacks an edge case to cover invisibility, stealth, and unseen enemies that lurk in darkness, but perhaps this can be interpreted dietetically. In ACKS II, this is formalized as the “I’ve Got a Bad Feeling About This” Memorial Rule, in which characters unable to sense opponents still make a surprise roll, and on a success can act normally on the basis of their subconscious perceptions and intuition. Likewise, if dice tell us that a hidden undead army exists just on the edge of civilization but there’s been no hint to this as yet, we might naturally assume they’re hidden and in torpor to explain it.

In the final case, we may be able to restore isomorphism by improving our model to create a better simulation. This may involve changing our threshold of abstraction to account for more (or less!) factors, or we might incorporate greater variability in the model to account for possible extremities. Changing the mechanics to better align with the game world is important but also a cause for great care, to ensure that we improve the situation instead of introducing new externalities.

Ultimately, this approach serves to provide what is in my opinion the best return on investment for the Judge. It focuses worldbuilding towards gameplay, and channels gameplay through the aspects considered interesting. I don’t think it is necessarily Simulationist — it seems beyond contest that non-Sim games implement such ideas — but it is certainly not anti-Sim and it is very principally consistent therewith.

Wherever in setting and rules there is particular detail, gameplay will tend to settle. If it settles elsewhere, it will be unsatisfying until the proper depth is established. Understanding the consequences and implementations of that seems to be near the heart of the Simulationist-Gamist synthesis that attains both, as every game should strive to. I am certain another dimension can incorporate Narrativism in that grand design, but what it is so far eludes me.